How Will You Measure Your Life…and Build Great Products?

How Will You Measure Your Life…and Build Great Products?

At first glance, it seems counter-intuitive that the two parts of the question would be related to each other.

How Will You Measure Your Life?, written by Clayton Christensen, is about how one can be successful, and happy in one’s career; how can relationships be a source of continuing happiness; and how can one live a life of integrity. Given Christensen’s prior much-acclaimed work, The Innovator’s Dilemma, and other contributions to business literature, this title is surprising. But he addresses the very core of personal and professional life. Christensen also draws great parallels to how organizations make strategic choices about allocating resources while evaluating the opportunities and challenges they face.

In Chapter 2, titled, “What Makes Us Tick”, Christensen talks about the importance of getting motivation right. In almost all organizations, incentive systems, mostly financial, are put in place to align individual employee objectives with those of the organization, with the goal of motivating employee performance. He cites Frederick Herzberg’s research in motivation theory.

We tend to think of job satisfaction as a spectrum, with happiness on one end, and absolute misery at the other end. But this is not how the mind works, because the opposite of job dissatisfaction is not job satisfaction, but it is just the absence of job dissatisfaction. This is why it is possible to love our job and also hate it at the same time.

Is this similar to customer satisfaction with our products? We measure customer satisfaction with surveys and net promoter scores, but do we fall into the trap of thinking that because our customers aren’t dissatisfied with our products, that they must be satisfied?

Christensen explains Herzberg’s theory further, saying there are two factors that affect motivation, hygiene factors and motivation factors. Hygiene factors are those elements of the job, that if not done right, cause dissatisfaction, e.g., compensation, work conditions, company policies, relationship with manager and colleagues, etc. Bad hygiene causes dissatisfaction, and must be addressed and fixed.

The important insight from Herzberg’s research is that if you instantly improve hygiene factors of your job, you are not suddenly going to love it. At best, you won’t hate it anymore.

Is this similar to how we build or improve a product, creating what we believe customers want, but find that customers don’t necessarily love our product immediately? Is it because customers are just simply hating the product less?

So what are the factors that cause us to truly love our jobs, and cause customers to truly love the products we build for them?

Herzberg’s research calls them motivators. In product development, we talk about things that delight customers. On the job front, motivation factors include challenging work, recognition, responsibility, and personal growth. What are the delighting factors of our products? The theory of motivation suggests that we should ask a different set of questions when we are evaluating our jobs and careers than we typically do. Similarly, are we asking the right questions when we are evaluating what features to prioritize in our products? Are our products simply addressing basic needs, or hygiene factors, that must be provided, but are not enough to create delight?

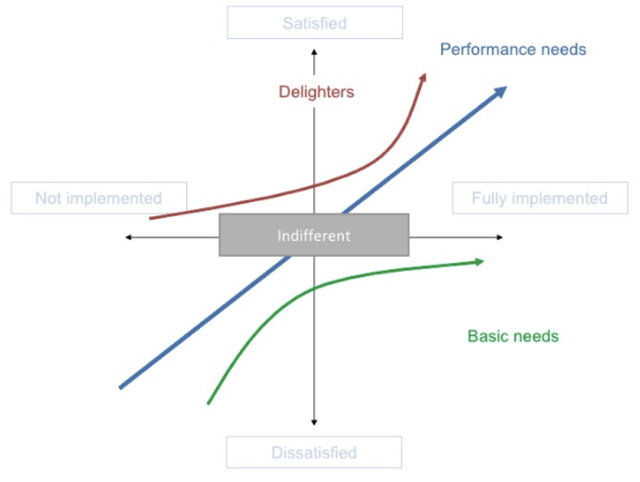

This is very similar to Kano Analysis of evaluating product features and capabilities. I don’t know if Kano Analysis was directly influenced by Herzberg.

How Will You Measure Your Life?, written by Clayton Christensen, is about how one can be successful, and happy in one’s career; how can relationships be a source of continuing happiness; and how can one live a life of integrity. Given Christensen’s prior much-acclaimed work, The Innovator’s Dilemma, and other contributions to business literature, this title is surprising. But he addresses the very core of personal and professional life. Christensen also draws great parallels to how organizations make strategic choices about allocating resources while evaluating the opportunities and challenges they face.

In Chapter 2, titled, “What Makes Us Tick”, Christensen talks about the importance of getting motivation right. In almost all organizations, incentive systems, mostly financial, are put in place to align individual employee objectives with those of the organization, with the goal of motivating employee performance. He cites Frederick Herzberg’s research in motivation theory.

We tend to think of job satisfaction as a spectrum, with happiness on one end, and absolute misery at the other end. But this is not how the mind works, because the opposite of job dissatisfaction is not job satisfaction, but it is just the absence of job dissatisfaction. This is why it is possible to love our job and also hate it at the same time.

Is this similar to customer satisfaction with our products? We measure customer satisfaction with surveys and net promoter scores, but do we fall into the trap of thinking that because our customers aren’t dissatisfied with our products, that they must be satisfied?

Christensen explains Herzberg’s theory further, saying there are two factors that affect motivation, hygiene factors and motivation factors. Hygiene factors are those elements of the job, that if not done right, cause dissatisfaction, e.g., compensation, work conditions, company policies, relationship with manager and colleagues, etc. Bad hygiene causes dissatisfaction, and must be addressed and fixed.

The important insight from Herzberg’s research is that if you instantly improve hygiene factors of your job, you are not suddenly going to love it. At best, you won’t hate it anymore.

Is this similar to how we build or improve a product, creating what we believe customers want, but find that customers don’t necessarily love our product immediately? Is it because customers are just simply hating the product less?

So what are the factors that cause us to truly love our jobs, and cause customers to truly love the products we build for them?

Herzberg’s research calls them motivators. In product development, we talk about things that delight customers. On the job front, motivation factors include challenging work, recognition, responsibility, and personal growth. What are the delighting factors of our products? The theory of motivation suggests that we should ask a different set of questions when we are evaluating our jobs and careers than we typically do. Similarly, are we asking the right questions when we are evaluating what features to prioritize in our products? Are our products simply addressing basic needs, or hygiene factors, that must be provided, but are not enough to create delight?

This is very similar to Kano Analysis of evaluating product features and capabilities. I don’t know if Kano Analysis was directly influenced by Herzberg.

The x-axis is how well features are implemented in the product, from not at all to fully well. The y-axis is how satisfied or dissatisfied customers feel. Features are categorized into different buckets.

Products must fulfill basic needs, or have the basic feature set, so that it is at least the minimum viable product. If the basic features are not implemented well, that can result in dissatisfaction, much like the hygiene factors of our jobs. As we move along the curve where basic features are implemented very well, we are just meeting expectations but not exceeding them. Our customers just hate our products lesser and lesser.

Products must fulfill basic needs, or have the basic feature set, so that it is at least the minimum viable product. If the basic features are not implemented well, that can result in dissatisfaction, much like the hygiene factors of our jobs. As we move along the curve where basic features are implemented very well, we are just meeting expectations but not exceeding them. Our customers just hate our products lesser and lesser.

A friend recently mentioned that she was quite frustrated at having to spend 30 minutes with a 7 page long manual, and still not able to reset her pedometer. Now being able to reset a pedometer would qualify as a basic need. In this case that feature was not well implemented, resulting in dissatisfaction with the product. Had she been able to do it quickly and easily, it would have been good, but not enough to be ecstatic and go shout out the product from the rooftops.

Products also have some “performance” features, where the performance of those features falls along a continuum, e.g., hours of battery life, amount of memory, 3-9s to 5-9s scalability, etc. Note we aren’t talking about more features, necessarily, but the range of values for the features themselves.

In case of the pedometer, the basic model may be able to remember my activity for 7 days, but the advanced model may be able to remember my activity for 22 days. Omron, which is a popular pedometer, has multiple models with different tracking modes. The one with two tracking modes costs $22.99, with four tracking modes costs $26.99, and one with six tracking modes costs $34.99. There are some other differences between those models but you get the point. It is well established and understood that product variations with “more performance” generally cost more, as there is more “value for money”. We pay more for the 64GB iPhone than the 16GB one.

The manner in which performance features are implemented also can be a source of dissatisfaction or satisfaction. But it does not become a source of delight. This is because, as a customer, I have paid to obtain that level of performance, so I am entitled to it.

So what is it that causes customers to be delighted?

What if the pedometer, in addition to simply counting the number of steps I have walked, gently beeps if I am within 10% of exceeding my previous best? What if it motivated me to walk more? What if it detected that I have been sitting down for too long and gently beeped to remind me to get up and walk around for the sake of my posture and health? Wouldn’t that be wonderful?

About motivation factors on the job, Christensen writes

Feelings that you are making a meaningful contribution to work arise from the intrinsic conditions of the work itself. Motivation is much less about external prodding or simulation, and much more about what’s inside of you, and inside of your work.

I have bought only a few pedometers in my life, and not one recently. I typically use one for the first few days, but not much beyond that – because it just meets the basic needs, most times, not even well. They don’t try to understand and respond to my true motivation of buying a pedometer, which is “I need to walk more”, and not “I need to count my steps”. Almost all the pedometers that I have seen on the market just stop at counting my steps, to put it simply.

Delight factors can create so much goodwill that customers can almost turn a blind eye to something else that you may have chosen to not do at all or not very well. A great example of this is the absence of Flash support on the iPhone and iPad. At the D8 conference, Walt Mossberg asked Steve Jobs about why Apple had chosen to not support Flash, that customers might feel that the iPad was crippled. While Apple had a variety of reasons, Steve said that this was an issue only to people in the Valley, and that customers outside of the Valley, for the most part weren’t having this issue, and Apple had been selling one iPad every 3 seconds – implying that the large majority of customers who bought iPads were loving them and were indifferent to lack of Flash.

There are different techniques in use to prioritize features. Many times features are grouped by some higher-level subsystem or the functionality they provide together, however, the Kano model is a good way to group features based on customer expectation. So as we make prioritization decisions about what features to include in our products, it is important to ask if we are simply meeting basic needs, and we better do that well, or can we really understand the intrinsic needs and delight customers. Can we make the tough calls to leave things out of our products and not invest time, money and energy in those that customers are likely to be indifferent to?

While I leave you with these questions to think about for your products, I’ll go back to learning more about how to measure my life

Share this:

In case of the pedometer, the basic model may be able to remember my activity for 7 days, but the advanced model may be able to remember my activity for 22 days. Omron, which is a popular pedometer, has multiple models with different tracking modes. The one with two tracking modes costs $22.99, with four tracking modes costs $26.99, and one with six tracking modes costs $34.99. There are some other differences between those models but you get the point. It is well established and understood that product variations with “more performance” generally cost more, as there is more “value for money”. We pay more for the 64GB iPhone than the 16GB one.

The manner in which performance features are implemented also can be a source of dissatisfaction or satisfaction. But it does not become a source of delight. This is because, as a customer, I have paid to obtain that level of performance, so I am entitled to it.

So what is it that causes customers to be delighted?

What if the pedometer, in addition to simply counting the number of steps I have walked, gently beeps if I am within 10% of exceeding my previous best? What if it motivated me to walk more? What if it detected that I have been sitting down for too long and gently beeped to remind me to get up and walk around for the sake of my posture and health? Wouldn’t that be wonderful?

About motivation factors on the job, Christensen writes

Feelings that you are making a meaningful contribution to work arise from the intrinsic conditions of the work itself. Motivation is much less about external prodding or simulation, and much more about what’s inside of you, and inside of your work.

I have bought only a few pedometers in my life, and not one recently. I typically use one for the first few days, but not much beyond that – because it just meets the basic needs, most times, not even well. They don’t try to understand and respond to my true motivation of buying a pedometer, which is “I need to walk more”, and not “I need to count my steps”. Almost all the pedometers that I have seen on the market just stop at counting my steps, to put it simply.

Delight factors can create so much goodwill that customers can almost turn a blind eye to something else that you may have chosen to not do at all or not very well. A great example of this is the absence of Flash support on the iPhone and iPad. At the D8 conference, Walt Mossberg asked Steve Jobs about why Apple had chosen to not support Flash, that customers might feel that the iPad was crippled. While Apple had a variety of reasons, Steve said that this was an issue only to people in the Valley, and that customers outside of the Valley, for the most part weren’t having this issue, and Apple had been selling one iPad every 3 seconds – implying that the large majority of customers who bought iPads were loving them and were indifferent to lack of Flash.

There are different techniques in use to prioritize features. Many times features are grouped by some higher-level subsystem or the functionality they provide together, however, the Kano model is a good way to group features based on customer expectation. So as we make prioritization decisions about what features to include in our products, it is important to ask if we are simply meeting basic needs, and we better do that well, or can we really understand the intrinsic needs and delight customers. Can we make the tough calls to leave things out of our products and not invest time, money and energy in those that customers are likely to be indifferent to?

While I leave you with these questions to think about for your products, I’ll go back to learning more about how to measure my life

Share this:

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

Trending Posts

Tagged blogs